Alexandria County Slave Births, 1853-1859

The following information has been drawn from the Birth Index of [Virginia] Slaves, 1853-1866 compiled by employees of the Work Projects Administration (originally the Works Progress Administration) between 1936 and 1939. The index, in turn, was transcribed from original manuscript records of births submitted as required by the Commonwealth of Virginia beginning in 1853 and subsequently retained by the state's Bureau of Vital Statistics. The index is a 337-page, typescript document in tabular form that is available today on microfilm from, and at, the Library of Virginia. It is arranged by the surname of the slaves' owners (or the name of others who may have reported the births to the state). The entire index has now been transcribed and edited by Leslie Anderson Morales and Ada Valaitis for publication in a series of seven volumes to be published by Heritage books in 2007. At this writing, the first volume, covering owner surnames beginning with the letters A, B and C, is available. The record below, however, is drawn directly from the microfilm, which will explain any discrepancies between the sources. The microfilm images are generally light, and the original pages may have been partly faded, rendering many entries illegible (and in one case below, the entry was partly obscured in the original manuscript ledger when the WPA tried to read it). Any mistakes are attributable to this cause or to the haste of your transcriber. For nearby Fairfax County, Virginia slave births, see African-American Births in Fairfax County, 1853-1859.

The birth entries for Alexandria County comprise a tiny portion of the overall state index. One reason is that, formerly just a piece of the 100-square-mile federal District of Columbia, the county-now known as Arlington County, but then also including what is now "Old Town" Alexandria and environs-was and remains the state's smallest in area. With the town of Alexandria, it was one of the most densely populated of the then 148 counties (prior to the Civil War-era creation of West Virginia), but it still ranked 40th in terms of total population in 1860. Many of Alexandria's enslaved African Americans had been sold south to the Mississippi Valley cotton and sugar plantations as the demand for labor there pushed up slave values, and the less agriculturally productive upper South fretted about the security implications of a large black population. As a fairly urbanized county experiencing a trend toward decreasing farm size, Alexandria's slaves frequently lived one or two to a white household or as a handful in a factory or shop, in contrast to the large field labor forces common on plantations elsewhere in the state. Although urban slaves often exercised greater physical freedom and more opportunities to earn cash by hire, outside supervision in a small city and their dispersal into white homes may have discouraged sexual relations between slaves. And although slave births created value for their owners, the support of children prior to their laboring years had to have been seen as an economic burden particularly in an urban area, and pregnancy likely a disadvantage to a household servant even in the household of a relatively compassionate master or mistress. The index undoubtedly undercounts the actual births, however, judging from the lack of thoroughness and the tardiness implied in the reports.

Births excerpted for a single county unfortunately provide a limited picture. The entire index-in its microfilm or ultimately published form-provides not only additional slave births into the war years (from the Confederate-controlled counties) but also possible connections between slaves owned by the same slaveholder but living in different counties. Even more important, it provides names and owner information for all the counties of Virginia and West Virginia, allowing for a single locale such as Alexandria the possibility of connecting migrant freed people back to their places of birth.

The order of the index information has been altered because the original entries had been by name of owner. The table below is arranged by date largely because, with only 85 births recorded, the order is perhaps less important as the names can be viewed at a glance and searched with a browser. It consists of four columns: date of birth (often approximate and sometimes possibly indicating instead the date of recordation); the name of the infant or a description, such as "male," "female," or "stillborn"; the name of the mother; and the name of the slaveowner or other informant, such as "former owner, overseer, employer, [or] guardian." If no name or other information was supplied in a column, then "not given" appears here.

Tim Dennée, April 28, 2007

D.O.B. |

Name or description |

Mother’s name |

Owner or other informant |

|

|

|

|

1853 |

Charles |

Malvina |

H.L. Monroe |

1853 |

Charles |

Ann |

John T. Evans |

3/1853 |

Frank |

Margaret S. |

W[illiam] A. Hart |

6/1853 |

female |

Mary Cole |

J. Summers |

7/1853 |

Thomas |

Sarah |

J[ohn?] T.B. Perry |

|

7/15/1853 |

Margaret A. Jones |

Julia Ann |

William Minor |

|

8/1853 |

Matilda |

Martha |

B.W. Hunter |

|

8/1853 |

Lucinda |

Susan |

E.D. Scott |

|

8/4/1853 |

Susan A. Crump |

Julia |

James Irwin |

|

10/1853 |

Alice Brown |

Maria |

A[nthony] C[harles] Cazenove |

|

10/1853 |

male |

Martha |

Thomas W. Swann |

|

11/1853 |

Charles |

Charlotte |

B.W. Hunter |

|

11/1853 |

Oscar |

Annette |

Edward Sangster |

|

11/1853 |

stillborn |

Caroline |

C. [or Susan] Shacklett |

|

11/8/1853 |

Jefferson |

Eliza Carroll |

Walker Harris |

|

11/10/1853 |

Charlotte A. Hyson |

Margaret |

William Minor |

|

11/22/1853 |

Sarah |

Sarah |

William King |

|

12/1853 |

stillborn |

Jane |

John Hollinsbury |

|

12/10/1853 |

John C. Calhoun |

Delia |

George N. Harper |

|

2/1854 |

stillborn |

Martha |

R[obert] S. Ashby |

|

4/25/1854 |

Lucey |

Susan |

W[illiam] B. Lacy [Lacey] |

|

6/1854 |

Anny Bailey |

Rachael Bailey |

William Minor |

|

6/1854 |

Edward Montgomery |

Ade[line?] Montgomery |

William Minor |

|

6/30/1854 |

female |

Malinda Bond |

N[ehemiah] Hicks |

|

7/1854 |

Martha |

Martha |

W[illiam] Bayne |

|

7/1854 |

Burrel Jackson |

Delilah J[ackson] |

George N. Harper |

|

8/1854 |

Roberta Logan |

Lucy Logan |

George [W.] Brent |

|

8/1854 |

Nuna |

Mary |

R.H. Huntson |

|

8/30/1854 |

female |

Malvina |

Jane Slaughter |

|

9/1854 |

Eve Devinport |

Alcinda |

Charles L. Adam |

|

9/1854 |

male |

Nicey Morgan |

E[lizabeth H.?] Gordon |

|

11/1854 |

female |

Sarah |

Nat[haniel] Clark |

|

1855 |

female |

Mary Cole |

J[ohn] Summers |

|

1855 |

Fanny Stuart |

Martha |

T.E. and M.A. Swann |

|

1855 |

John Adolphus |

Lucy Ann |

T.E. and M.A. Swann |

|

1855 |

Washington Mines |

S[arah] A[nn] |

T.E. and M.A. Swann |

|

3/1855 |

Lewis |

Susan |

R[obert] Brockett |

|

5/1855 |

Octavia Stafford |

Mary |

Joseph Ball |

|

6/1855 |

Drayton Bower |

Jenny Bower |

E[dward?] B. Addison |

|

7/1855 |

female |

Delia Watts |

Elizabeth [H.] Gordon |

|

8/1855 |

Edward Harris |

Arrena Harris |

Joseph Gregg |

|

9/1855 |

John W. Fair |

Genny (& Alfred) |

B[asil] Hall |

|

10/1855 |

female |

Ann Gardner |

A[nthony?] Frazier |

|

10/1855 |

George |

Sina |

A[nthony?] Frazier |

|

11/1855 |

male |

Nelly |

L.B. Hardaway |

|

12/1855 |

Lucy Carter |

Mary |

Samuel Burch [Birch] |

|

12/1855 |

female |

Martha Pleasants |

F[rancis] L. Smith |

|

1856 |

Dolly Ann Mitchell |

not given |

John Hart |

|

2/2/1856 |

Harrison |

Louisa |

Miss [Elizabeth?] Betsey Gordon |

|

8/18/1856 |

female |

Nelly |

John [R.?] Johnston |

|

9/17/1856 |

stillborn |

not given |

John Johnston |

|

11/3/1856 |

Mary Elizabeth Jackson |

Louisa J[ackson] |

John N. Harper |

|

12/29/1856 |

male |

not given |

A.E. Addison |

|

1857 |

female |

Elizabeth |

Charles Alexander |

|

2/4/1857 |

female |

Susan |

D[avid] S. Guinn [Gwinn] |

|

6/1857 |

male |

Harriott |

Nancy Jordon |

|

7/1/1857 |

Julia Carter |

Jane Ball |

J.W. Hollinsbury |

|

8/12/1857 |

male |

Catharine |

James A. English |

|

10/14/1857 |

Lucien |

Mary Smith |

Mrs. [Kitty?] Thompson |

|

11/1/1857 |

female |

Delilah [Jackson?] |

George N. Harper |

|

11/2/1857 |

female |

Harriett |

George N. Harper |

|

12/25/1857 |

female twins? |

Martha Hopkins? |

L.R. Roberson |

|

1858 |

not given |

not given |

B.W. Hunter |

|

1858 |

not given |

not given |

B.W. Hunter |

|

1858 |

not given |

not given |

B.W. Hunter |

|

1858 |

not given |

not given |

W.F. Lee |

|

1858 |

not given |

not given |

W.F. Lee |

|

1858 |

not given |

not given |

W.F. Lee |

|

1858 |

female |

not given |

John Stephenson |

|

2/1858 |

male |

Sarah Ann |

T.E. and M.A. Swann |

|

3/11/1858 |

female |

Ellen |

Mrs. S[ally?] Gordon |

|

4/4/1858 |

female |

Margaret |

Elizabeth Andrews |

|

4/19/1858 |

male |

not given |

George N. Harper |

|

7/7/1858 |

George |

not given |

J[ames] C. Beach |

|

9/20/1858 |

male |

Susan Willis |

W[illiam] W. Adam |

|

10/14/1858 |

not given |

not given |

B.W. Hunter |

|

12/6/1858 |

not given |

Mary |

T.E. and M.A. Swann |

|

12/11/1858 |

female |

Caroline |

Samuel O. Baggott |

|

12/15/1858 |

not given |

not given |

B.W. Hunter |

|

12/15/1858 |

Mary Jane |

Margaret |

J.E. Douglass |

|

1859 |

male |

not given |

B.W. Hunter |

|

1/4/1859 |

male |

Martha |

Mr. [William W.?] Adam |

|

4/1859 |

female |

not given |

B.W. Hunter |

|

4/7/1859 |

Mary |

Amanda |

J.H. Hollinsbury |

|

7/1859 |

female |

May |

Col. Robert E. Lee |

|

11/1859 |

male |

not given |

Col. Robert E. Lee |

|

12/21/1859 |

Lillie Jane |

Louisa |

J[ohn?] W. Campbell |

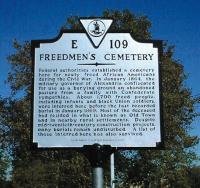

Mother and child at Smith's Plantation, Beaufort, South Carolina, 1862.

Photograph by Timothy H. O'Sullivan. Library of Congress.

|

Friends of Freedmenís Cemetery |

|

April 29th, 2007