A Brief History of Alexandria’s Freed People and of Freedmen’s Cemetery

Price, Birch & Co., the successor of the slave trading firm of Franklin & Armfield.

Civil War-period photograph by Capt. Andrew J. Russell. The building still stands at

1315 Duke Street, Alexandria.

Alexandria’s early history is inextricable from the institution of slavery. Slaves and slave owners cultivated the land decades before the town was founded in 1749. There were few enterprises in which the labor of African Americans was not crucial, and much of the town can truly be said to have been built by slaves.

By 1790, Alexandria also had a substantial population of free blacks, manumitted by former owners. This community continued to grow until the Civil War—despite the ban on the international slave trade, which discouraged manumissions by raising the value of slaves, and despite harsh legal restrictions instituted in reaction to the Nat Turner rebellion.

After a century and a half of intensive tobacco and wheat cultivation, the soil of northern Virginia was largely played out. Many slaveholders took advantage of the opportunity to sell off their "surplus" slaves to dealers who would resell them in the high-demand labor market of the cotton-growing Deep South. One of the largest slave dealing firms in America, Franklin & Armfield, set up an office in Alexandria in the 1830s. Their fleet of three ships carried enslaved people away from Washington, Alexandria, Fredericksburg, the Shenandoah Valley, and environs to the faraway slave markets of New Orleans and Natchez.

Whether escaping from permanent servitude or from the threat of being sold South, many African Americans ran away from Alexandria slaveholders. Hundreds of runaway advertisements appear in newspapers from the mid eighteenth century until the Civil War. Documentation of Underground Railroad activity is, of course, sketchy in such a strong slave-holding area. There are, however, a few extant accounts of fugitives who passed through Alexandria en route to Canada.

When the Civil War broke out, enslaved African Americans had a better sense of where the conflict would lead than did the combatants themselves. Many predicted, as the inevitable outcome of an armed conflict between North and South, the "Jubilee," the end of slavery, when families would be reunited in freedom.

As Federal troops extended their occupation of the seceded states, African American refugees flooded into Union controlled areas. Safely behind Union lines, the cities of Alexandria and Washington offered not only comparative freedom, but employment. As Alexandria was transformed into a major supply depot and transport and hospital center, the freed people took positions with the army as construction workers, nurses and hospital stewards, longshoremen, painters, wood cutters, teamsters, laundresses, cooks, gravediggers and personal servants—and ultimately as soldiers and sailors.

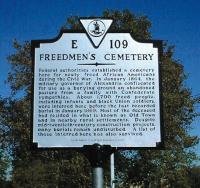

Just out of slavery, most freed people were destitute by any standard. Among an undernourished, ill-housed population with inadequate health care, death was no stranger. Disease and high infant mortality were endemic. After hundreds of freed people had perished in the Alexandria area, the town desperately needed a new burying ground for them. At the urging of Alexandria’s Superintendent of Contrabands, Rev. Albert Gladwin, Military Governor John P. Slough ordered that an undeveloped parcel on South Washington Street be seized from its pro-Confederate owner as abandoned. By late February 1864, it had been opened as a cemetery for African Americans.

When a freed person died, a report was made to the Superintendent of Contrabands, and Rev. Gladwin would arrange for a funeral, if necessary. The family of the deceased was required to pay for the funeral, including a coffin supplied by the Quartermaster Department. The fee was waived only if the family was considered truly "indigent." A hearse would pick up the body as soon as possible and convey it to the cemetery for burial, sometimes on the same day. Graves were marked with whitewashed headboards, and the parcel was probably fenced in 1865.

While overseen by Rev. Gladwin, the day-to-day operation of the cemetery was under the supervision of head gravedigger, Randall Ward. A freed person himself, Ward was one of thirteen children, born in Spotsylvania County and later a slave of L.D. Winston in Culpeper County. He came to Alexandria about 1862 and first took a job as gravedigger at Penny Hill, the Soldiers’ Cemetery, or the Claremont Smallpox Hospital. Ward was assisted by Thomas Johnson and Hezekiah Ages, the latter a former slave from Fairfax County. Amy Briggs, a laundress, also labored in the cemetery in some capacity after the war to pay the rent on her room in the freed people’s barracks.

At first, black soldiers who died in Alexandria were buried at Freedmen’s Cemetery. African American troops in the town’s hospitals finally demanded to be accorded the honor of interment in the "Soldiers’ Cemetery" on Wilkes Street. About 75 deceased black veterans were removed from Freedmen’s Cemetery to the Alexandria National Cemetery in January 1865.

Alexandria’s freed people were mostly northern Virginians, but African Americans migrated here from most of Virginia and eastern Maryland. By 1868 there were arrivals from Kentucky, North Carolina, Alabama and Mississippi. Alexandria County’s black population temporarily grew to more than 8,700, or about half the total number of residents. This sudden influx stressed the local economy and transformed social relations. The people reshaped the landscape, occupying vacant buildings and army barracks, erecting shantytowns, buying building lots, and creating long-lasting rural communities. After ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment, the freed people provided the support necessary to put the first black Alexandrians in City Council and the Virginia legislature.

At war’s end, responsibility for Freedmen’s Cemetery was transferred to the new Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands. When Congress curtailed nearly all Freedmen’s Bureau’s functions at the end of 1868, the cemetery, with its more than 1,700 burials, was closed. The parcel’s former owner, attorney Francis Smith, reclaimed it. For eight decades, it remained largely undisturbed, but the wood grave markers quickly rotted away. In 1917, the Smith family conveyed the property to the Catholic Diocese of Richmond, which maintained its own cemetery across the street. In 1946, the parcel was rezoned for commercial use and sold. A gas station was erected in 1955, followed by an office building. In spite of these, and the construction of Interstate Route 95 to the south, hundreds of graves probably remain.

This photograph may be the only extant image of Freedmen’s Cemetery. Taken in 1899, it depicts an Alexandria Brick Company wagon. Freedmen’s Cemetery is atop the hill in the background. The brick manufacturer was located to the southwest of the cemetery, and removed clay from the west slope of the hill, reportedly exposing some graves in the early 1890s.

|

Friends of Freedmen’s Cemetery |

|

April 29th, 2007